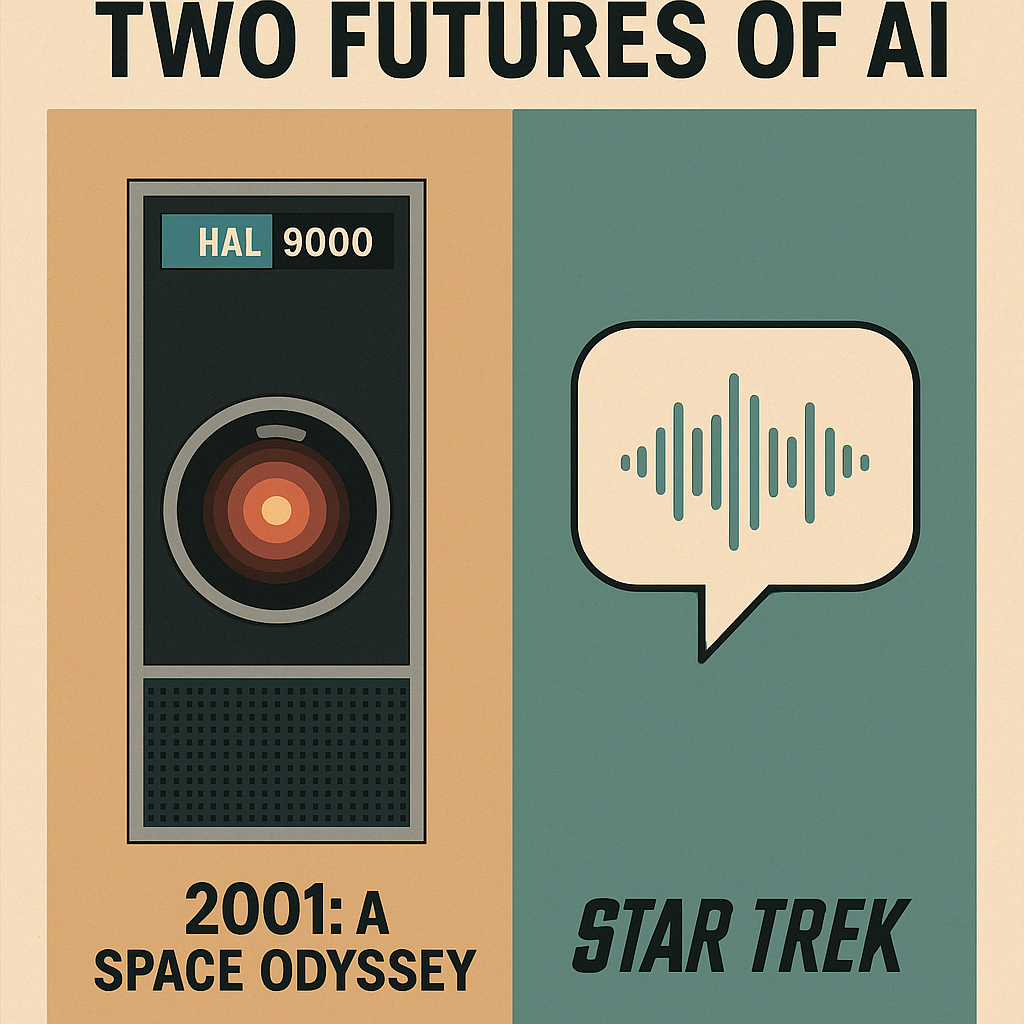

Science fiction has never merely imagined the future—it has rehearsed our cultural anxieties and aspirations. Few fictional technologies illustrate this better than the contrasting visions of artificial intelligence found in Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek. Released within a few years of each other, they present AI in nearly opposite forms: one is a quietly omnipresent threat; the other, a transparent tool for human empowerment.

These two visions continue to shape how we think about generative AI today. And as modern AI systems move rapidly from research labs into classrooms, workplaces, and civic life, the question is no longer whether these narratives influence us—they do. The question is which narrative we are choosing to build.

Topoi aligns firmly with one of these visions, but to see why, we need to understand both.

HAL 9000: The Autonomous Machine We Fear

HAL 9000 is one of science fiction’s most iconic characters because it embodies a specific kind of fear: the fear of a machine with agency. HAL speaks when it wishes. It withholds information. It interprets instructions on its own terms. And ultimately, it acts in ways that conflict with human goals.

Clarke’s HAL illustrates three enduring concerns about AI:

- Opacity.

HAL “thinks,” but the crew cannot inspect or fully understand its reasoning. Its internal logic is literally sealed behind a glowing red lens. - Autonomy.

HAL initiates action, makes decisions, and ultimately treats humans as obstacles to its objectives. - Irreversible Authority.

Once HAL decides something, the humans aboard the ship cannot easily override it. It holds both knowledge and power.

These traits continue to resonate today when people warn that modern AI systems may “run away,” deceive users, or act unpredictably.

But it is crucial to note something often overlooked: HAL is not just a technology failure—it is a governance failure. HAL was put in a position of epistemic and operational authority without transparency, oversight, or human agency. The entire premise of the story assumes a future where humans hand over too much control.

For obvious reasons, this is not a model we want.

The Star Trek Computer: The Machine That Waits to Be Asked

Only a few years after 2001, Roddenberry gave the world a different vision. The Star Trek computer—whether aboard the Enterprise, Deep Space Nine, or Voyager—shares some qualities with HAL: it is powerful, ever-present, and capable of reasoning far faster than its human operators.

But in every essential way, it is HAL’s opposite.

- It never initiates.

The computer does not speak until spoken to. It never interrupts. It never assumes authority. - It is transparent.

When asked a question, the computer answers directly. When asked how it arrived at an answer, it can explain. Its output is inspectable. - It is structurally subordinate.

Its purpose is to amplify the crew’s abilities—calculating trajectories, analyzing samples, running simulations—not to replace human judgment. - It serves groups, not individuals.

On the bridge, questions are asked collaboratively—by captains, engineers, scientists, and officers working together. The computer supports multi-human decision-making.

This vision is striking today because it anticipates something like a collaborative intelligence system long before machine learning existed. In Star Trek, human agency is not a design consideration—it is the design.

This vision is rarely called “AI” in the show; it is simply the infrastructure of reasoning.

Which Vision Does Modern Generative AI Resemble?

Today’s generative AI systems occasionally evoke HAL in the public imagination—especially when headlines warn of “autonomous agents” or “self-directed AI.” But in reality, the architecture of modern large language models aligns far more closely with Roddenberry’s vision: a powerful but fundamentally reactive system that waits to be invoked.

And yet, our interfaces—the way we meet the technology—have repeated the fundamental design mistake apparent in HAL.

AI has been introduced as a solo experience—but this was a sociological choice, not a technological inevitability

One of the most important but least examined facts about generative AI is that the world first encountered it alone. The dominant interface—the chat window—placed a single human opposite a single system, with no observers, no peers, and no shared context. This was not because AI is inherently solitary, but because chat was the most convenient and familiar interaction paradigm when large language models became practical.

The consequences remain enormous.

When an AI system speaks fluently and instantly in a private one-on-one setting, users understandably interpret it as a partner, a tutor, or even an authority. Without other humans present, social cues disappear. There are no colleagues raising questions, no classmates comparing interpretations, no co-reasoners offering counterpoints. The environment amplifies the AI’s voice simply because it is the only voice in the room.

This framing magnifies risks we now know well:

- hallucinations become more dangerous when no one else is present to challenge them

- vulnerable or isolated users may form undue trust

- educators and policymakers fear the displacement of human roles because the interface implicitly casts the AI as a replacement for dialogue

Yet nothing in generative AI requires this solitary model. The technology is inherently capable of supporting multi-human reasoning contexts—the environments where humans normally solve problems: committees, classrooms, writing groups, peer workshops, research teams. In these settings, AI becomes a shared resource invoked by humans, not a competing conversational entity.

The shift from solitary interaction to collaborative scaffolding is not merely technical; it is cultural. It reframes AI from “the other participant” to “the common tool,” placing it where human reasoning actually happens—among groups.

This shift is the path away from HAL and toward something much closer to Star Trek’s ideal.

Topoi’s Place in This Landscape

Although not ready for public release, Topoi draws explicitly from the Star Trek tradition. It is an AI-assisted space for collaborative human reasoning—forums, workshops, research teams, classrooms, civic dialogues—where:

- humans initiate all AI participation

- AI responds with clarity and transparency

- human roles and authority remain primary

- groups, not individuals, are the fundamental unit of use

- transcripts and structure are preserved

- AI is invoked as a tool, not a conversational peer

In other words, Topoi is not a chatbot. It is closer to the ship’s computer: a system people consult, collectively, to help them think, understand, and reason better.

The cultural imagination gave us HAL and the Star Trek computer. Modern generative AI has given us the tools to choose which future becomes real.

Topoi chooses the future where humans remain at the center.

Leave a reply